Country: Myanmar, {Burma}

I woke to the sound of rain hammering on the tin roof and to a slightly thick head from drinking home-brew rice wine with suspected terrorists. Despite this I began the trip towards the border town of Moreh with high spirits. I had begun to enjoy my time in India since crossing into the north east, but I still couldn't wait to get out. With only 110km to the Myanmar border, I was looking forward to splitting the trip into two easy rides. The rain got heavier. It didn't take long for me to be soaked again. It was still early and the hills were not as bad as expected, but enough to make me sweat inside my waterproofs. The possibility of getting to Moreh in one hit and taking a rest day the following day was in my mind. I pressed on. The road surface got worse. Then it stopped entirely.

The precipitation in the mountains had caused a pretty major landslide and as I was the only vehicle there it must have been fresh. I checked the map and confirmed that I was on the only road to the border. The only option was to clamber over mud and rocks with my laden bike trying to avoid slipping to my death, with small trickles of mud and stones from above me keeping me alert to the need to get out of there fast. The next slide did have vehicles on either side of the obstruction, and luckily for me, some of them were excavators, shovelling tonnes of mud from one side and dropping it down into the valley. I spoke to a man who smelt like he'd bathed in Jim Beam. Despite the language barrier, and his slurring, I ascertained he was the foreman of the operation and it would take five minutes.

Ninety minutes later, with the sun almost set, I continued. Shortly afterwards I was stopped at my third military checkpoint of the day, they were friendly and gave me some water. I asked if they had whiskey instead but they just laughed. I wasn't joking. I asked if there were hotels nearby and they told me that Moreh was the nearest and that I should just keep going.

This was the worst advice ever, it got incredibly dark amongst thick jungle on either side and dense cloud cover overhead. On top of that the road was still dogshit. It was at least downhill, but there was no choice but to ride the brakes constantly as spotting the potholes (or rather, the spaces between the potholes) was nigh on impossible in the lashing rain.

There was nowhere even remotely suitable for camping so I had no choice but to struggle on. The only benefit to the terrible road was that locals obviously knew not to bother, there were no other vehicles for hours, improving my chances of survival significantly. When a minivan finally did show up, it slowed to a stop. A figure fell out of the passenger door and greeted me warmly with a handshake and a bottle of local hooch. I took it. I then accepted their offer of a lift to town. With a bicycle hanging between the two open side doors, three men in the front and Tokyo (the driver) unable to change gears properly with my leg in the way, we screeched around the muddy hairpins in whatever gear it happened to drop into with his friend (who’s name I have sadly forgotten) passing me more Sake in an old Coke bottle to warm me up.

It turned out town was actually only about two kilometres away, making me irritated for caving and accepting their assistance. The lights of Moreh were a beautiful sight as we crested a hill (in fourth). I was imagining a shower and putting on my final set of dry clothing, airing all my crap out and taking a day off tomorrow. Before we could enter this city of dreams of course was a military checkpoint. The excitable young guard ran around on a power trip reporting the late-night arrival of a tourist. His friend in the watch tower fired off a load of rounds in celebration. I was flattered. Then came the sobering news that I wasn't allowed through tonight, it was too late.

“What?! This isn't the border, is it?!”

“No. Just checkpoint. My sergeant says you come tomorrow”

“Piss off. I'm soaked and knackered. I want a hotel.”

“Tomorrow”. He wasn't going to budge.

“Oh fine, whatever. I'll just sleep here then” I pointed to the deck

“No. Go back”

“What?! To where?! The road is falling apart and I can't see anything”

The guard shrugged. It was obvious he didn't care.

Tokyo offered to drive me back to a village. 1 kilometre before where he'd picked me up. How the hell had I missed a village? There must have been no power. I questioned whether fate was punishing me for taking the lift.

We screeched to a stop (in fourth) on the T-junction in the middle of the village and me and Tokyo went to find the chief. He was friendly to begin with. Tokyo then spoke to him in Hindi, explaining my situation. The chief went apeshit and disappeared, I assumed that I would not be happily hosted here. Tokyo explained that the chief was disgusted that I had been refused and had left to call the checkpoint to find out who was responsible. I was welcome to sleep in the village hall, an offer which I quickly accepted.

The hall was already playing host to four or five local men laying under mosquito nets who we later found out were road workers who operate excavators, like the ones I met earlier, and as their job required call outs to wherever the road was least usable at the time, they were somewhat nomadic and used village halls as temporary accommodation. I also saw two bicycles with a pile of panniers accompanied by two men laying in sleeping bags on the floor.

“Are you two Argentinian?” I asked, somewhat obscurely.

“Erm, yes” Replied the older of the two. I had finally caught up to the other cyclists ahead of me.

About two weeks earlier, at a police checkpoint, I had filled in a register with my details (as was an almost daily requirement). Above my name was the details of two Argentinians who, as the book showed, were also destined for Myanmar. I inquired if these guys were travelling by bicycle too, the police confirmed it and twice more I saw their names above mine, but never saw them on the road. Had the army let me through into Moreh, I likely wouldn't have seen them again either. A small blessing. I hadn't seen another cyclist in two months.

We spent the night there and, presented with even worse weather in the morning, decided to wait another day. We were 10km from the border and my permit wasn't valid until the following day anyway. The locals treated us like royalty, giving us tea and inviting us to eat with them at every meal. We dried our gear, cleaned and repaired our bikes and chatted about the cruddy road.

The following day the sun was back. We hit the road at about 8am and messed around with more checkpoints for a while. Eventually, we reached one that might have been the border (it wasn't, but the guards claimed it was). The man with the slowest penmanship in the world had been assigned the task of taking the details of those passing through. After Lucas and Horatio had had theirs taken, they asked for their exit stamps. The guard pointed back down the road we'd come from...

“You don't keep the exit stamp here at the exit?” Lucas asked.

“Go to SGPO in town for stamp”

While he wrote my details, the Argies headed back to find the no-doubt illusive 'SGPO'. In turn, I ventured back towards town, expecting to find my friends still in search of the office, I found some guys in military fatigues and asked for directions, they had no idea what I was talking about. I asked some more, they pointed me down an alleyway. I found an office. Of sorts. I knocked on the doorpost and went in. Nobody. I walked through and out the back door, calling out. Nobody. I went back and a guy walked in, gave me a bottle of water and asked me to sit. We chatted, I asked about the stamp a few times. Another guy entered. He took me through the back door and out to a picnic table. He explained that this was customs and I should have come here first, despite it being invisible to the untrained eye. He took my details, which, as I pointed out, were still identical to the ones I had given every other bloody official that day. No search was conducted and no customs related questions asked. He walked me over the road to the SGPO and found his colleague, who had come back from eating lunch or having a bath or something, still playing Candy Crush on his phone.

We chatted and I gave him my details too, which I now know by heart. I pointed to the computer and explained that they can be used for storing and sharing data, like passport and visa details, over huge distances. Across one town would be very simple really. Even more simple would be for him to play Candy Crush closer to the exit. I got my stamp.

It's always amusing to enter a small shop at a border town and make their day rinsing off all your excess currency from that country; the usual essential supplies of instant noodles, water and 15p packets of cigarettes were secured and I rode back down to the “exit” gate, where the guards had changed shifts, the new guard wanted my details again. I bypassed the process by flicking back through the book on his desk to the details I had given thirty minutes prior. He was confused. I had already left, how had I re-entered India? I raged at him that this was why they should keep the fucking stamp at the exit. He backed down and let me go. Onwards, to Myanmar. Nope. The REAL exit gate came first. Thankfully, these guys were content just to see my exit stamp and asked, half-arsedly, if I was transporting drugs. I was finally out of India.

I have never seen such chaos at a border.

I followed some signs and the vague hand wave of a Myanmar soldier, and found what looked like an abandoned school. Outside were Horatio and Lucas' bikes, they'd made it. Well, very nearly, I could see they were not happy.

“Do you have a permit letter?” Horatio asked me.

“Yeah, we CAN go through, right?” I was nervous, I could no longer re-enter India. Then I realised that his question implied they didn't have a permit.

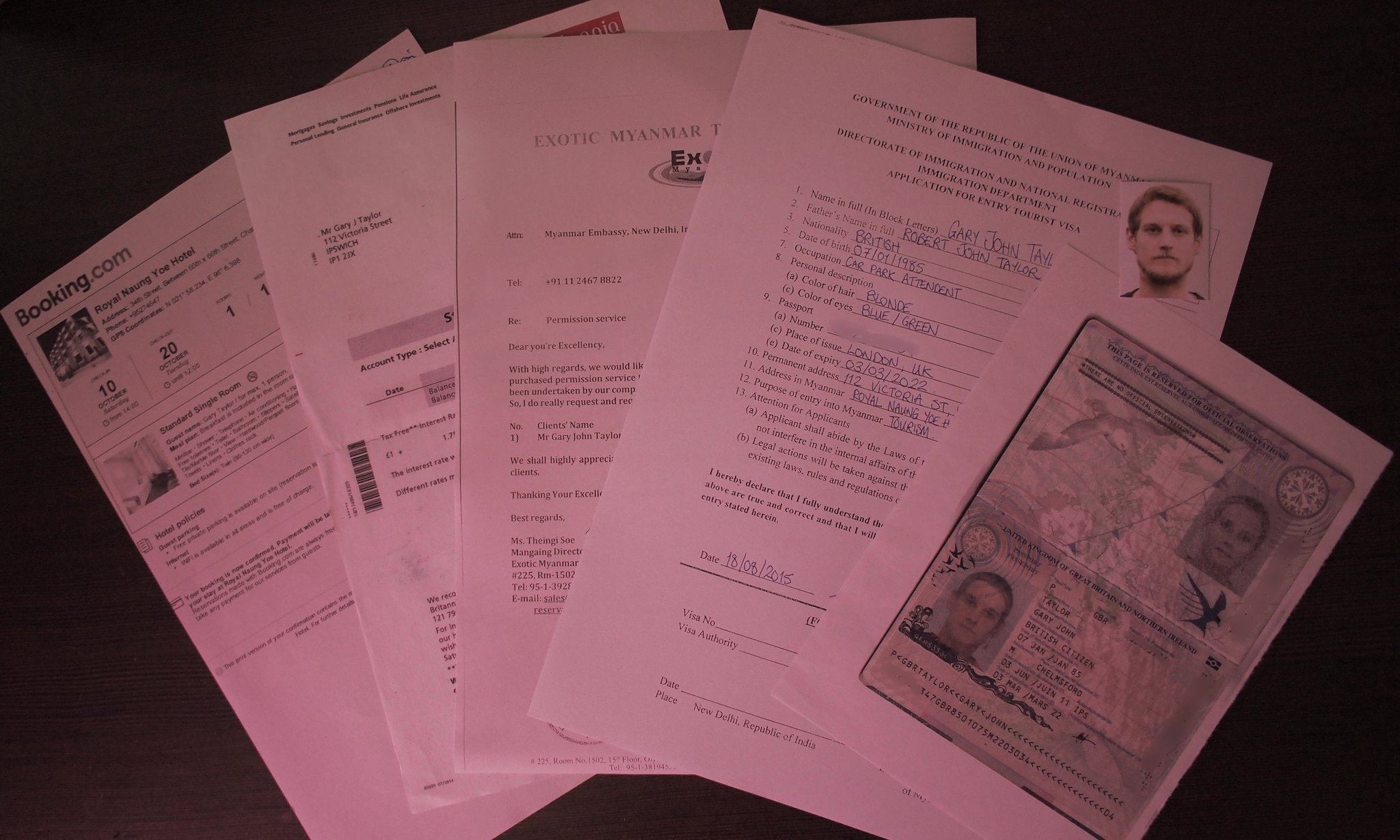

I'd mentioned the permit to them, but I guess it was lost in translation and they had assumed I meant a visa. Without a permit they were unable to cross the border into Myanmar. Their plan to travel East to Thailand was now impossible by land, as all other borders in the area are closed. I felt terrible for them. And for me, I was looking forward to having some company again. Our riding partnership had lasted only 10km. A semi-official looking chap handed me his phone and a really confusing conversation between me and a mystery caller took place, something about broken bridges, travel agents and a guest house. They told me not to stay in monasteries or camp, which is of course exactly what I intended to do so I ignored it.

Me and the Argentinians talked a bit about their options and how they could get a permit, and whether they should just cross illegally. A guy on a moped appeared and was asking me to follow him to town. I realised that the agent I'd arranged my permit through had sent him, probably to take me to his cousins guest house or something. I told him I could find my own way, but first I needed to actually get my entry stamp. So I went into the empty school.

There was a bloke sitting at a desk looking like he was waiting for his students to return from lunch. He took forever to check my permit and my passport whilst I imagined sitting between the two countries eating dry noodles and drinking from puddles hoping my government would airlift me home. I had exited India and could not re-enter on my old visa, nor could I get a new one here. Consuls and border staff seem to have mastered the art of building suspense when it matters; they check and re-check everything, ask questions in a tone which makes you feel guilty, make twisted expressions that give the feeling that you missed something, or got a date wrong. Then, after that, they painstakingly prepare the stamp and hover with it over the page for an eternity before finally applying it.

After the usual cock-tease rigmarole he stamped it. With tomorrow's date. I pointed to the error, he smiled and said “OK, today is free”. He applied another stamp to show the expiry date. He got that one wrong too. That one he corrected by stamping over it. I realised with this level of professionalism, Lucas and Horatio could probably get away with stamping theirs themselves. Or drawing it on in crayon or something.

Lucas and Horatio decided to do the legal thing so we said our goodbyes and they headed back into India. Luckily for them they had multiple entries on their Indian visas. I followed my moped escort towards Tamu, finally in Myanmar! He took me to a hotel, where I was again mysteriously handed somebody's mobile phone. A man's voice started explaining something about broken bridges, guest houses and monasteries. They were adamant that I shouldn't go towards Mandalay that day, it was dangerous, illegal or expensive, or all of the above. I was annoyed and pretty sure they were conning me, so I told them I would go where I liked, but thanked them for the warnings. I really didn't want to stay here, I was confident that they were just bullshitting me to make me stay in one of their partner hotels.

I set about trying to change my money with the hotel staff, they said they would, I began changing money, over the phone agreeing the exchange rate with somebody, and passing the phone to the hotel manager who then typed the numbers into a calculator and changed the money from the till. I was happy with the rate. The money changer hotline then began to explain that I should not stay in monasteries. I hung up, more determined than ever to stay in a monastery that night. Then I saw it.

The familiar humming of glorious refrigeration surrounded the glass and metal cuboid, stood alone in the corner, rammed full of cans of delicious, ice cold beer. Throughout the north-east of India, alcohol was prohibited, and thus prohibitively expensive. The only liquor available was bottles of whiskey at nearly twice the price of the UK from under the counter in restaurants and hotels. I bought a beer with my new wedge of Myanmar Kyat. And sat with the hotel staff. I asked how much it was to stay and decided I wouldn't leave today. At 18km. This must have been my least productive day of riding yet.